Dear Friends,

My teacher the late Rabbi Ira Eisenstein liked to say that Judaism is a 3,000-year-long discussion of ethics. That is to say, the essence of Judaism is the never-ending process of trying to figure out what is the right thing to do.

This is hard. It is hard because life is complicated. It is hard because life is a continuous balancing act of caring for and about ourselves and caring for and about others. Yes, the Torah presents us with lists of rules that should be simple enough to follow. “Do not murder” is clear. But then we must apply the rule: can we murder someone who is about to murder us? What if they are about to murder our family? What about during wartime – do these rules change in times of war? And so, if we are thoughtful people who want to make ethical choices we inevitably must examine and discuss each moral rule as it applies to situations as they arise. This is how we make ethical choices. All ethics are applied ethics, and are necessarily conditional and imperfect. That is, whatever the ideal and succinct principle or commandment might be, the pressing task of ethical people is to make the best possible choices in inherently complicated circumstances. Then, as we observe the results of our decisions, we reevaluate our choices, and adjust them if called for. We own our missteps. We apologize and make amends. We do the best we can.

The famous words of Rabbi Hillel capture this complexity, and I consider them to be the best encapsulation of Judaism’s “mission statement:”

הוּא הָיָה אוֹמֵר: אִם אֵין אֲנִי לִי, מִי לִי? וּכְשֶׁאֲנִי לְעַצְמִי, מָה אֲנִי? וְאִם לֹא עַכְשָׁיו, אֵימָתָי?

Hu hayah omer: Im ein ani li, mi li? U’kh’she’ani l’atzmi, mah ani? V’im lo akhshav, eimatai?

Rabbi Hillel would teach:

If I am not for myself, who will be for me?

And if I am only for myself, what am I?

And if not now, when?

(Teachings of the Sages 1:14)

For me, these pithy, melodic words merit endless contemplation and reflection. Like all true wisdom, they embrace paradox, bear multiple interpretations, and demand that we live inside these questions. How do we dance this dance of self and other? How do we honor and protect ourselves and still offer our best to others? And if not now, when?

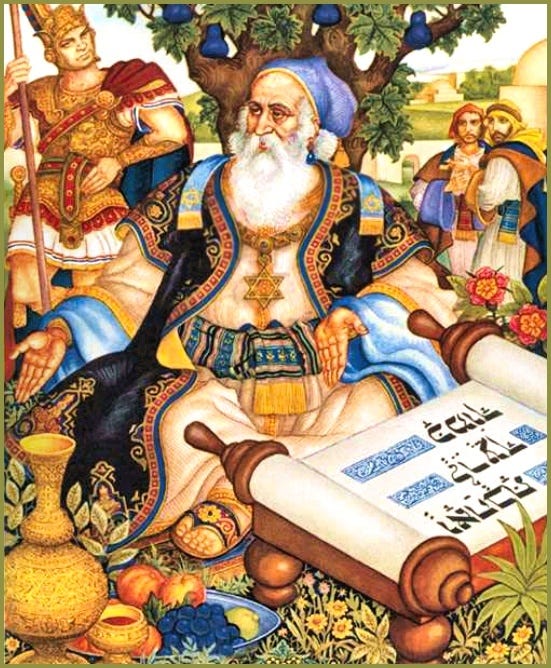

I call these words Judaism’s mission statement not only because of their power, but because of Hillel’s exalted position in Jewish history. Hillel stands as the key founder of the rabbinic tradition, and his teachings carry extra authority. He lived in the 1st century BCE. We do not know many facts about his life, but the lore that emerges describes a spiritual master of humble origins who was kind, humorous, and wise. His aphorisms are like a rich meal, and need to be digested. Hillel taught, “In a place where there are no human beings, strive to be a human being.” He taught, “Do not judge another until you have stood in their place.” He taught, “Love peace and pursue peace, love all human beings and [in this way] draw them close to the Torah.” He taught, “What is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow; all else is commentary. Go and learn.”

As the catastrophic war between Israel and Hamas continues to wreak death and destruction, battle lines have also been drawn around the world, with masses of people rigidly taking up sides. Battle lines for and against Israel have been drawn within the Jewish world as well, as we are all too painfully aware. I think Hillel’s teaching demands that we not take binary “us” versus “them” stances.

History certainly teaches us Jews that “If I am not for myself, who will be for me?” And as it feels like the world is once again arraying itself against us, many of us understandably want to close ranks and only ensure our own survival. These deeply concerned Jews insist that this is what Judaism demands. But that cherry-picks Hillel’s teaching. Similarly, many Jews whose hearts are breaking over the suffering of Palestinians in Gaza take only the second part of Hillel’s teaching as their rallying cry – “If I am only for myself, what am I?” – and these deeply concerned Jews insist that this is what Judaism demands.

Both camps are wrong. Judaism demands that we do both. Judaism demands that we stand up for our own survival and well-being, and that we at the same time concern ourselves with others’ survival and well-being. Nothing less. For me, Judaism is a tradition worth studying, practicing, and preserving precisely because it makes these seemingly impossible ethical demands on us. In a world gone dangerously mad, Judaism demands that, however imperfectly, we hear and enact not part, but all of Hillel’s teaching. This is the Jewish mission statement.

And if not now, when?

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Jonathan Kligler

Lovely. Thank you!

As always you covered all the bases for a home run! Thank you Rabbi Jonathan for sharing your heartfelt & wise perspective on the human dilemma of self and other.

It’s a Blessing to have had you in my life.